In a podcast with Rhonda Patrick[1]Dr. Benjamin Levine: How Exercise Prevents & Reverses Heart Aging, Dr Benjamin Levine, an exceptionally accomplished sports cardiologist, according to Patrick – says that you cannot use heart rate variability, in answer to her question about it’s use for training. He resorts to mendacity to make his point.

Firstly, he states that “I published probably 100 papers about cardiovascular variability”[2]Dr. Benjamin Levine: How Exercise Prevents & Reverses Heart Aging. Note, he does not say heart rate variability – but given that it’s in response to a question about HRV, that’s what he implies.

Do a search on Benjamin Levine and heart rate variability. The only thing that comes up in the results is this podcast. Levine has not published a single paper on heart rate variability.

He then goes on to make a number of statements about measuring HRV. He talks about how breathing affects HRV. He’s right. You can see it when you looking at the graph while taking a reading. Change your breathing pattern and it has an impact on the graph. We have analysed the data, and there is no correlation between the rMSSD figures and the respiration rate, but there is also no question that changing your breathing affects the reading.

Levine discusses the various frequencies and states that “heart rate devices is (sic) mostly looking at the high frequency variability”.

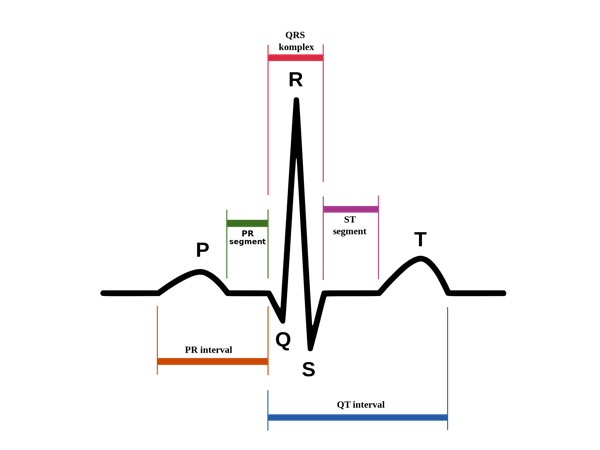

This is complete nonsense. The pulse rate has a wave form, seen in the graphic above. The parts of the wave are titled PQRST, with the highest point being the R. All devices that measure HRV, measure the interval between one R point and the next – known as the R – R or inter beat interval (IBI). The frequencies are measured by analysing the patterns in the variability in the IBIs.

The analysis of these patterns is the real science behind HRV.

Levine compounds his dishonesty by resorting to discrediting Heikki Rusko, who is one of the leading researchers on HRV, and it’s use in sports science. He refers to a paper the Rusko wrote almost twenty years ago that was inconclusive in its attempt to use HRV to measure recovery. Since then Rusko has written numerous papers that use HRV to reliably measure recovery[3]Heart rate variability dynamics during early recovery after different endurance exercises.

The Poincaré plot[4]Understanding the Poincaré plot is a powerful indicator of a person’s state of health. Within the plot, the length and width of the graph and the patterns in these metrics over time give us a reliable way of recommending recovery status. It’s not perfect, but it does work.

Levine is correct that measuring HRV needs to be done under consistent, almost clinical conditions to be reliable. One can see that he is taking aim at the wearable market, Garmin and Whoop. All the variables of day to day living in the data that a wearable records makes it impossible to provide reliable results. In that, he is correct.

But then he implies that even under clinical conditions, HRV does not work. He says “ I can’t get better than a plus or minus 25 percent day to day variability.” What does that mean? Which metrics is he looking at to get this result? If he were looking at the Poincaré plot, and using those metrics, like Rusko, he would get better results.

Courtesy of one of our users we have become aware that the World Champion French women handball team uses HRV for recovery[5]Sylvain Fréville – Tout sur la variabilité de la fréquence cardiaque.

Rhonda Patrick has an impressive following – people who trust her. To regain her credibility, she needs to research the subject, and offer a correction.

The Dallas bed rest and training study

The Dallas bed rest and training study, originally titled Response to Exercise After Bed Rest and After Training is a seminal paper that changed the approach to bed rest for recuperation, and that reduced activity, and not age alone is the cause of many of the symptoms associated with ageing[6]A re-analysis of the 1968 Saltin et al. “Bedrest” paper.

The study measured the impact of 20 days of bed rest followed by almost eight weeks of intensive exercise, with metrics including a number of physiological adaptations on five subjects, two of whom were athletes, and the remaining three who were normally active[7]Response to Exercise After Bed Rest and After Training. One of the few criticism of the paper was the small sample size.

In her interview with Dr Levine, Rhonda Patrick, in her introduction incorrectly states that he was part of the study. Levine quickly corrects her, pointing out that he performed the 30 year study on the same five subjects, and was not involved in the original study. The 30 year study has limited scientific value. There is no formal methodology of measuring the exercise that the subjects undertook in the intervening period, and so is nothing more than a measurement of the extent of change in the 30 years that had elapsed. Giving this limitation, the 40 and 50 years studies that have since been performed, appear to lack real scientific purpose.

What is notable however is that it is these studies, and not the original paper that an Internet search returns when trying to find the Dallas best rest and training study.

Levine says that the 5 subjects “were the five most studied humans in the history of the world”. This is hyperbole, and has no place in a scientific discussion. Not only that, it’s wrong. Anyone familiar with the work of Bengt Saltin, the principal author of the Dallas bed rest and training study, would be familiar with his other studies, particularly that of why athletes from a small tribe in Kenya have dominated middle and long distance running, and the study of which have been larger and more intensive[8]The Kenya project – Final report. It also bears little comparison to the studies of the modern professional athletes, particularly those who are members of the leading professional cycling teams.

The Cardiac Effects of COVID-19 on Young Competitive Athletes

Dr Levine goes on to discuss the ORCCA study[9]The Cardiac Effects of COVID-19 on Young Competitive Athletes: Results from the Outcomes Registry for Cardiac Conditions in Athletes (ORCCA). He makes the point that 0.06% of the sample had symptoms that lasted more than twelve weeks. Two out of the 1600. But the maths is wrong. That’s because the sample was actually 3,600 making it the biggest study of it’s kind to that point in the USA.

More importantly Levine states that the reason for this low figure is “because as soon as they got over their quarantine period, because they were in a competitive environment, they quickly returned to a trainer, a monitored and implemented return-to-play program.” The study does not mention that anywhere.

Moreover, that conclusion contradicts Dr Levine’s paper which advises a cautious approach towards return to exercise after contracting COVID[10]Icarus and Sports After COVID 19: Too Close to the Sun?.

Dr Levine has a promising future in politics.

References